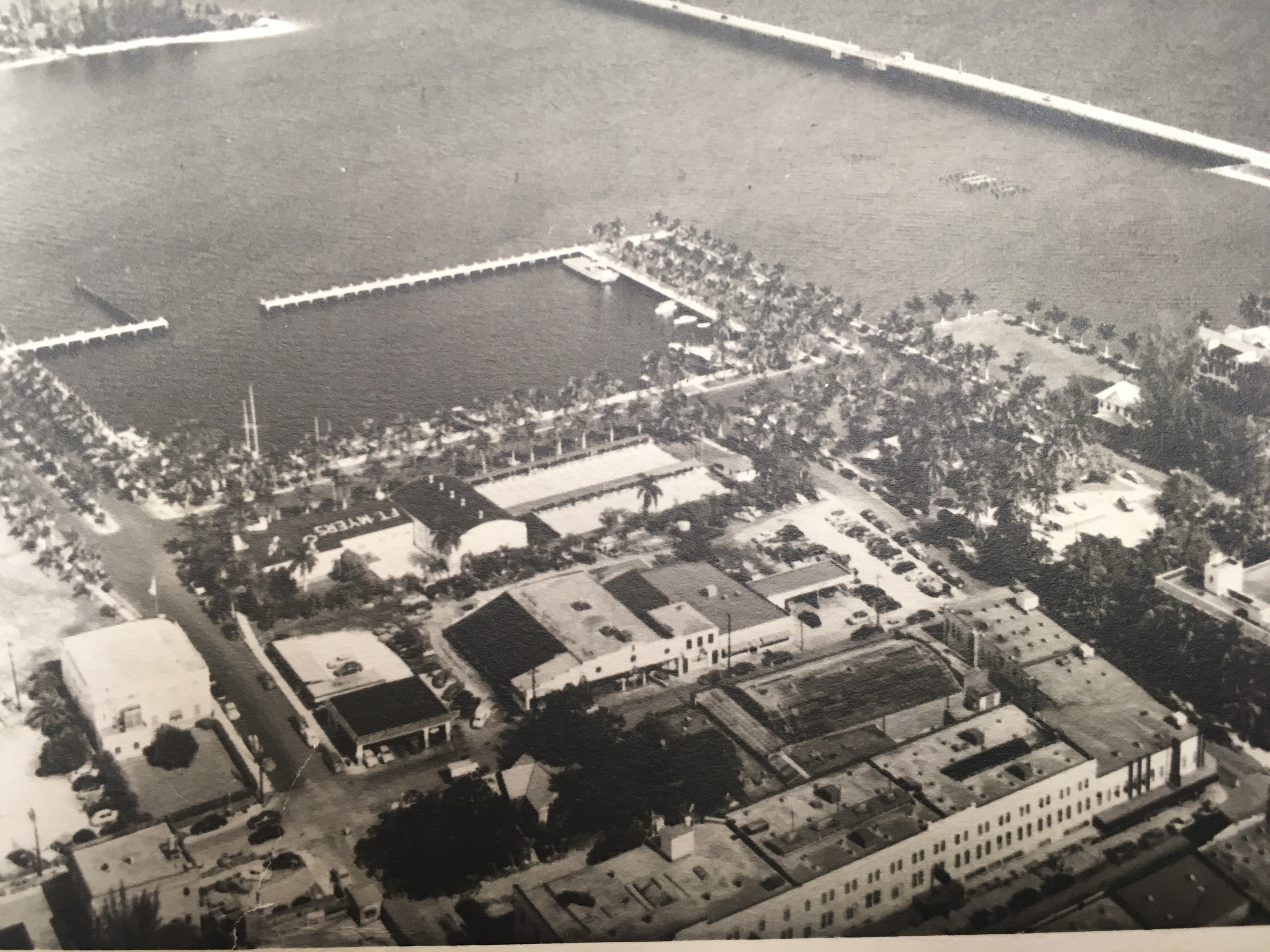

We spent much of May 2021 docked in Ft Myers, Florida. The temperatures were in the balmy 80’s and it hardly rained at all. Back in 1875, there were only about 350 people living on the banks of the Caloosahatchee River. Air conditioning would not be invented for another quarter century. This rare view of the Ft Myers waterfront (above) was taken around 1875-1880 and hangs on the wall of the Southwest Florida Historical Society. It is startling realize that today, the state of Florida is the third most populated state in the country. But back in 1875, it ranked about 33rd . Florida was only admitted to the union in 1845 as the 27th state. So the growth of Ft Myers is very much a 20th century phenomenon.

The waterfront has changed dramatically over the last 100 years. When we approached the basin of Ft Myers from the Caloosahatchee River, the buildings on the waterfront were formidable and modern. Some appear over 35 stories high. Based on the census of 2020, some are projecting the population of the county will exceed 100,000 within the next few years. Real estate is booming. Only a few years ago, an article in US News and World Report identified Ft Myers as the #1 place to retire. The area has been described as one of the fastest growing in the country. It seems hard to appreciate that only a century ago, the waterfront looked quite different.

In the 1920’s, ramshackle docks were all that existed of the harbor. By the 1930s however, the population was approaching 10,000, and a WPA project led to a modern basin built of fixed cement encircled with palm trees. The mangroves featured in earlier images of the area had all but disappeared. Today, the Ft Myers Yacht Basin still looks remarkably like the basin of the 30s but with additional docks. The harbor is safely tucked on the south side of Caloosahatchee, a little more than 16 miles inland from where the River meets the Bay–on Florida’s Gulf Coast. Historically, this inland location provided safe protection from hurricanes.

So what is the history of this town? In the early 1800s, the young United States was at war with the Seminoles. Over 250 forts were constructed across the future state of Florida. At the end of the War of 1812, John Quincy Adams negotiated Florida away from Spain, and future President Andrew Jackson aggressively led the US Army into the territory. During those early years, Ft Harvie (which would become Ft Myers) was one of the hundreds of Forts. Harvie had a reputation for being quite lavish as forts go. Even so, it was mostly made of local yellow pine (unlike the sturdy edifices that still survive in some other parts of Florida). In 1841, Ft Harvie was renamed Ft Myers for a brevet Colonel Abraham Myers, who became a quartermaster for the growing young nation’s objectives (as led by the US Army). The story goes that Col Myers was honored with a fort in his name mostly because he married well (the daughter of an important Major General from Tampa). However, it is said that Myers never actually set foot in the fort bearing his name.

Arriving by boat, it is not obvious where this original fort stood (pine buildings don’t wear well in the harsh Floridian environment, nor survive when local settlers scavenge for lumber). With a little digging for information, it seems that archeologists have pegged the Fort as being approximately where Hough, Monroe and Second streets are today. These streets that are essentially next to the yacht basin.

By 1858, the brutal Seminole wars were over, and Fort Myers was abandoned. The last of the 124 natives were removed to Arkansas. Then, a brief reoccupation of the Fort occurred during the Civil War when 400 Union soldiers moved into newly refreshed barracks. The Northern war strategy involved blockading the entire southern Atlantic coast to the furthest southern points of Florida–the Keys, and then up inside the Gulf coastline. Control of the Mississippi River was part of the war strategy. The goal was to cut off Confederate supply lines and trade. Among other things, this action effectively interfered with the delivery of cattle raised in central Florida, which was much needed by hungry Confederate soldiers. (Florida’s history of cattle ranching may not have been as romanticized in the way “the West” was in 20c filmography, but it was every bit as colorful–but that is another story.)

While occupying Ft Myers, Union soldiers also raided local beef ranches, and disrupted Confederate blockade runners (Florida was a Confederate slave state). They also welcomed escaped slaves into the ranks at the Fort. Then, at the close of the war, the Fort was once again abandoned, and by most reports, evacuated quite efficiently. Despite this relatively brief Union occupation, the county where Fort Myers remains was subsequently named for Confederate General Robert E. Lee in 1887 (Lee County, FL).

Although finding the fort in “Ft Myers” is mostly about events that occurred in early American military history, the story of the little port town is also shaped by much earlier territorial history; along with industrial era innovators who built their winter homes along the River.

Long before the Seminoles were driven out by the Army of the new United States in the 1800s, Calusa natives dominated estuarian waterways of the Caloosahatchee River thriving on a diet of fish and oysters. The name of the Caloosahatchee that flows in front of Ft Myers basin pays homage to these ancient peoples (hatchee meaning river.) Some estimate the Calusa were in the region as early as the year 500. They were the ones whom Spanish conquistador Juan Ponce de Leon encountered when he arrived at La Florida roughly between 1513-1521. The Calusa are also credited with mortally wounded the conquistador, but Spain later won the somewhat passive aggressive war when they managed to appeared to deceive and then assassinate the fierce Calusa leader “King” Carlos around 1566. (Spellings of the Calusa King’s name vary and are remarkably similar to Spain’s own King of that period, Charles/Carlos). After that, the presence of these ancient Calusa seemed to virtually disappear.

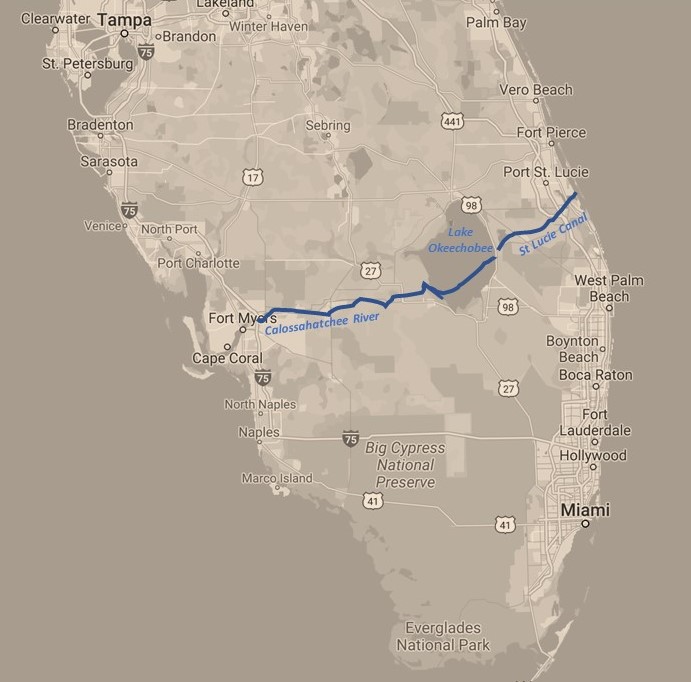

Much more recently (in the last few centuries) American investors envisioned broadening and connecting the Caloosahatchee River with the freshwater Lake Okeechobee Lake (Seminole for Oki Chubi or “big water”) connecting it to the Kissimmee River Valley; and then dredging a canal to connect to the St Lucie River to the East. The latter, providing an efficient traverse from the Gulf of Mexico to the Atlantic across the lower middle section of the state of Florida. The vision was probably not uniquely American. The hardy Calusa were known paddle into the interior of what the Spanish named La Florida, portage canoes where necessary, and travel far up into the Kissimmee River Valley for centuries before Ponce de Leon arrived.

Today, the implementation of the American vision is summarily referred to as the Okeechobee Waterway. It first started becoming a reality when wealthy young Hamilton Diston arrived around 1881 in Ft Myers with an innovative dredge and his dreams of progress. Steamboats appeared soon after. The canal that connected the Lake to the St Lucie River to the west was not completed in 1916, however. This exercise in human engineering was further “improved” by WPA initiatives which created the Hoover Dike around the Lake, the basin at Ft Myers, and other projects in the area. Further civil engineering projects are still happening today. We saw lots of giant machinery moving the land along the banks of the Waterway.

To be honest, we found this 156+ mile crossing convenient for our cruising adventures. It involved negotiating 5 locks and 11 active bridges and offered sufficient, although relatively shallow water of 8-10 feet most of the way. Sadly, the many anthropomorphic changes made in the last century have induced significant environmental challenges for residents of Southwest Florida—both for indigenous populations of all kinds as well as of the human kind. Even so, when we made our own crossing, alligators still slipped off the shoreline in front of our bow, and abundant brown cattle with Spanish conquistador ancestry foraged along the green scrubby shoreline.

After air conditioning became more readily available in the 20c, Ft Myers appears to have begun its growth spurt in earnest. The popular tourist and commercial establishments around Ft Myers basin today seem mostly inspired by the innovation and wealth of Thomas Alva Edison and Henry Ford, who made their winter homes in Ft Myers. Other names which define the shoreline tend to honor or recognize wealthy cattlemen and railroad developers of the 1800s.

When we came into the harbor of Ft Myers, the remnants of the Fort, and the thousand years of Calusa heritage were not obvious. They survived in name only: as of the Basin and the name of the River. The downtown area adjacent to the Basin is distinctively marked as an “historic,” but the American history of Edison and Ford are the things that that are featured prominently. Popular music booms from local roof top bars. The nature of Fort Myers original buildings are probably best understood by visiting the local historic society. To be fair, in order to find more evidence of the Calusa heritage, we probably needed to cruise a little bit further West toward the Gulf—and maybe visit Charlotte Harbor, Sanibel, or south to Marco Island area. Perhaps next year?

References

https://cityftmyers.com/civicalerts.aspx?AID=1179

https://www.jstor.org/stable/30149384?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents/ (Giveaway Forts: Territorial Forts and the Settlement of Florida, Ernest F. Dibble, 1999)

https://www.jstor.org/stable/30148691?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents (Southern Extremities: The Significance of Fort Myers in the Civil War,Irvin D. Solomon, 1993)

https://fortmyers.floridaweekly.com/articles/archaeology-tour-reveals-history-of-fort-myers/